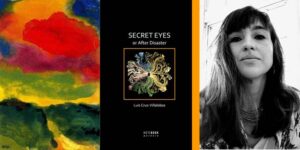

From the Center of the World

Contemporary Poets of Ecuador

Selected, translated and introduced by

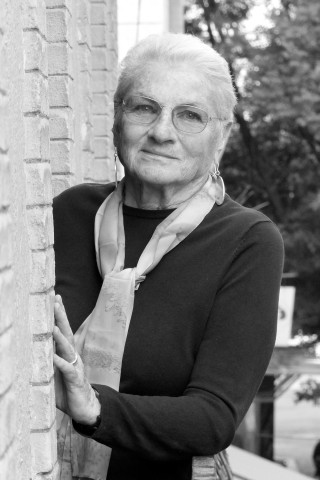

Margaret Randall

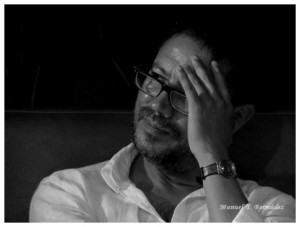

MARGARET RANDALL

COURTESY OF PASCUAL BORZELLI

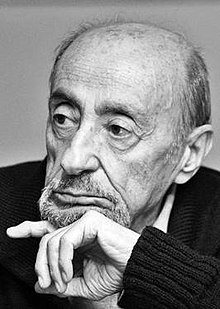

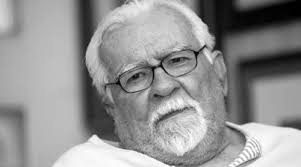

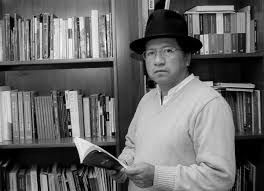

JORGENRIQUE ADOUM (1926-2009)

Historia

Al comienzo, la patria

fue una gran página en blanco:

la arena, el mar, la superficie,

la sombra verde, la tinta

con que manchó el invierno la sabana.

Pero de pronto, sin que nada

pudiera detenerlo, hay un hombre

conduciendo a su familia por los márgenes,

entra, cae y escala hasta el renglón

ecuatorial buscando vida.

Yo vengo desde allí: desayuné con ellos

en la primera mañana de mi pueblo,

construimos sembríos contra el hambre,

un río de cereal llevamos a la harina

y supimos las leyes del agua y de la luna.

De la segunda página hasta hoy día

no hay sino violencia. Desde

el segundo día no hubo día

en que no nos robaran la casa

y el maíz y ocuparan la tierra

que amé como a una isla de ternura.

Pero mañana (mucho antes

de lo que habíamos pensado)

echaré al invasor y llamaré a mi hermano

e iremos juntos hasta la geografía

—el dulce arroz, la recua del petróleo—

y le diré: Señora, buenos días,

aquí estamos después de tantos siglos

a cobrar juntas todas las gavillas,

a contar si están justos los quilates

y a saber cuánta tierra nos queda todavía.

History

In the beginning, the nation

was a great white page:

sand, sea, surface,

green shadow, ink

winter staining the sheet.

But suddenly, as if nothing

could stop him, there is a man

leading his family along the edges,

he enters, falls and climbs

to the equator searching for life.

I come from that place: ate breakfast with them

on my people’s first morning,

we planted fields against hunger,

shaped wheat into a river of cereal

and knew the laws of water and the moon.

From page two until the present

there is nothing but violence. From

the second day there wasn’t one

when they didn’t rob our homes

and corn and occupy this earth

I loved like an island of tenderness.

But tomorrow (long before

we thought possible)

I will vanquish the invader, call my brother

and together we will find geography

—sweet rice, petroleum’s flock—

and I will say: Good day, Madam,

here we are after so many centuries

ready to gather all the sparrows,

make sure they weigh what they should

and learn how much land we have left.

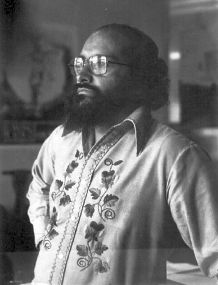

MIGUEL DONOSO PAREJA (1931-2015)

Regreso

a mi Madre

Estamos hoy muy cerca y sin embargo lejos.

En mis grises designios de amargas latitudes

fui dejando tus besos sepultados de olvido.

Y me he quedado solo,

mirando la verticalidad pretérita

de un poste desplomado,

o la horizontalidad en crisis de los senos

de una moza olvidada.

Y como dos extraños,

sin besos y palabras hermosas,

separando un abismo nuestro amor verdadero,

voy alargándome hacia ti

por el cordón umbilical de una mirada perdida,

como este puerto mío que se alarga en su ansiedad de océano

vengo a rogar tu amor y a dejar mi promesa

por un mejor mañana.

Tengo la sal de mi naufragio, tengo

una piedra en el alma y en los ojos

una ansiedad preñada de caminos,

una implacable sed; en las entrañas

y sobre el corazón y en el cerebro

tengo el azúcar de la tierra porque tú me la has dado.

Hay tantas cosas.

Tantas verdades que se escapan a los ojos

porque un beso nos amarra, en la distancia, la mirada.

Tantas verdades que se niegan,

porque hay un mar que llora abrazado del alma,

… y un doler

y una borrachera en la que vivo un mundo inaccesible,

inalcanzable,

como la ingenua sonrisa de una niña loca.

Madre hoy vengo a ti angustiado.

Con la angustia de un libro maltratado por un torpe

o un hombre esperando en una esquina

a la mujer de otro.

O el que escucha en la sala de una clínica,

su alimentado semen en el llanto de un hijo.

Vengo tímido y vengo avergonzado.

Con la timidez y la vergüenza de una sonrisa sin dientes

o un joven masturbándose.

Con la vergüenza de una niña desnuda

por primera vez ante los ojos de un hombre.

Con la vergüenza de un libro en la vitrina

que no es comprado nunca.

Vengo llorando.

Dejando al viento mis lágrimas de hijo

para que se unan al inmenso sistema de tu tanto

formado por tus lágrimas de madre.

Estarás orgullosa porque seré otro hombre

y he matado mi triste soledad y mi llanto

y ahora son las distancias y las acciones buenas

y aunque estamos muy cerca y sin embargo lejos

yo haré que esta acidez se convierta en dulzura

y de esta despedida sin viaje volveremos

para darnos un beso cuando estemos de vuelta.

Return

to my Mother

Today we are so close yet so far from each other.

On my gray journeys to bitter latitudes

I left your kisses buried in oblivion.

I remain alone,

gazing at the vertical history

of a fallen post

or your breasts in the horizontal crisis

of an abandoned boy.

And like two strangers,

with neither kisses nor beautiful words

separating the vast expanse of our love

I leave, wandering toward you

along the umbilical cord of a lost look,

like this port of mine that moves off on its ocean of anxiety

I come to plea for your love and promise you

a better tomorrow.

I taste the salt of my shipwreck, there is

a stone in my soul and in my eyes

the fraught tension of this passage,

insatiable thirst; in my gut

and heart and mind I hold

the sweetness of my land, your legacy.

There is so much.

So many truths that escape my eyes

because we are joined by a kiss, in the distance, by a look.

So many truths denied,

for there is a sea that cries embracing my soul,

. . . and pain

and the drunkenness in which I exist in an inaccessible world,

unreachable,

like the innocent smile of a crazy little girl.

Mother today I come to you in anguish.

The anguish of a book tossed aside,

a man waiting on a corner

for another man’s wife.

Or one who in a clinic hears

his fortified semen in the cry of his son.

I come to you hesitant and humiliated.

With the fear and shame of a toothless smile

or young boy masturbating.

The shame of a naked young girl

standing before a man for the first time.

With the shame of the book in the window

no one ever buys.

I come in tears

and deposit my tears of a son in the wind

that they may join the immense system of everything

created by your mother’s weeping.

You will be proud because I will be someone else.

I have killed my sad loneliness and weeping

and now there are distances and good deeds

and although we are close yet far away

I will turn this bitterness to sweet

and from this motionless goodbye we will return

to kiss one another when we are home again.

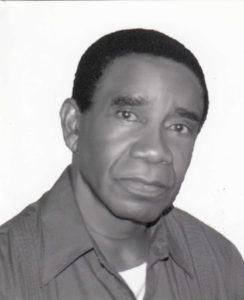

ULISES ESTRELLA (1939-2014)

Piedras vivas

Si vinieron del Volcán

estas piedras

trajeron el Fuego

del contorno

al centro,

muy adentro

están fortificadas

desde los bordes

llaman a las caricias,

a descubrir los impulsos

apenas con el tacto

de quienes quieran descubrir

las fiebres internas.

Si fueron expulsadas

desde el fondo de la tierra

son quiteñas sustancias,

Piedras Vivas

que acompasan

los ritmos antagónicos

de nuestros corazones.

Semejantes a cabezas humanas

podrían haber salido de la Caverna

en busca de espacios donde apoyarse.

Living Stones

If they came from the Volcano

these stones

brought Fire

from circumference

to center,

deep inside

they are powerful

at their edges,

calling on caresses

to discover desire

with the simple touch of those

who search for hidden flame.

If they were expelled

from the depths of the earth

their substance belongs to Quito,

Living Stones

in step with

the antagonistic rhythms

of our hearts.

Like human heads

they might have emerged from the Cave

looking for a place to rest.

ANTONIO PRECIADO (1941)

Anima primera

Todas las noches salgo

a hablar con los fantasmas.

Todos llegan a tiempo con el viento

agitando sus nombres

en una multitud desesperada.

¡Ah!

Juana la lavandera

solo anda en noches claras.

Siempre me llega en lunas,

lunas,

lunas,

chapoteando el agua.

Ved que me lavan los ojos,

que me enjuagan la palabra

veintiún manos azucenas,

con agua de nueve charcas.

Ángel, ¿quién enjabonó

trece veces tus dos alas?

¿Entiendes, Dios, la blancura

de tu espléndida garnacha?

¡Guardián del noveno cielo,

llueve una lluvia de nácar,

porque Juana ensangrentó

una punta de su sábana!

First Soul

Every night I go out

to speak with ghosts.

All show up on time, wind

rustling their names

in anxious multitude.

Ah!

Juana the washerwoman

only comes on clear nights.

She always arrives with the moon,

the moon,

the moon,

sloshing about in water.

Watch as they bathe my eyes,

twenty-one lily hands

rinsing my word

in the water of nine pools

Angel, who thirteen times

lathered up your two wings?

God, do you understand the clarity

of your splendid grape?

Guardian of the ninth heaven,

a mother of pearl rain falls,

because Juana bloodied

the edge of the sheet!

ANA MARÍA IZA (1941-2016)

Lobo azul

No quise detenerte

pensaste que era el viento

la fuerza de gravedad que te empujaba

Y era el impulso mío

la sed de lo que parte

Bien puede ser

el sol tras la montaña

o la montaña en sombra desteñida

la ciudad que se esfuma en la ventana

la estela en barco convertida

el olor de los muelles

la hora cero

la caída del Dios que nos levanta

La dulzura de las manos solas

la mancha

en los pañuelos blancos

No quise detenerte

me gustabas por agua

Llévate el lobo azul

Déjame el lila pálido

Blue Wolf

I didn’t want to hold you back

you thought it was the wind

the force of gravity pushing you

And it was my impulse

thirst of what goes away

It might as well be

the sun behind the mountain

or the mountain in blemished shade

the city disappearing in the window

the comet transformed into a boat

the odor of the docks

zero hour

God’s fall that lifts us

The sweetness of hands alone

the stain

on white handkerchiefs

I didn’t want to detain you

I loved you in water

Take the blue wolf

Leave the pale lily for me

RAUL ARIAS (1943)

Que las palabras piensen,

se enternezcan, duerman, sueñan y despierten.

Que saliven como gatos ante la leche.

Que oigan alegres el estallido de los cohetes

en una fiesta popular.

Que jueguen como niños en la calle.

Que se saluden en un portal, guareciéndose de la lluvia.

Que las palabras continúen diciendo palabras

y usen pañuelos de colores en el cuello.

Que salgan de sus casas y se conecten

como hilillos de aire o de agua,

pequeños trozos de carne fluyente.

Que, antes que nada, luchen por las otras,

por las encarceladas en la ignorancia

o en las cárceles mismas.

Que las palabras piensen mejor cada día,

que amen la palabra libertad y la defiendan.

Que aprendan a odiar la palabra imposible

y no teman lo desconocido.

Que las palabras peleen, se alisten y desfilen.

It is true, words think,

are tender, sleep, dream and wake.

They salivate like cats before milk,

get excited when fireworks go off

at a community fair.

They play like children in the street.

They greet you in a doorway,

sheltering themselves from rain.

Words keep on uttering words

and wear colored handkerchiefs at their necks.

They leave their homes and merge

like delicate threads of water or air,

small flowing chunks of meat.

Before all else, they fight for the others,

those imprisoned by ignorance

or by brick and mortar prisons.

Each day words have deeper thoughts,

they love and defend the word freedom.

They learn to hate the word impossible

and are not afraid of the unknown.

Words struggle, get ready and fall into line.

SARA VANEGAS (1950)

tu nombre . . . deja una cicatriz de naves incendiadas

aquí. en el océano de mi pecho

*

el cortejo de lunas es ya un recuerdo en tus ojos náufragos

la noche nos juntará en lo más hondo:

como un aullido

*

el fantasma de tu voz

aún me llama

hoy

por un nombre ya olvidado

*

en ciertas noches del año—dicen—emerge sobre la superficie del océano una ronda de delfines dorados formando extraños mensajes . . .

la luna entonces se va tornando azulada. lentamente

*

dicen que cuando la luna está azul brotan ciudades enteras del fondo del mar. que sus habitantes (de ojos fosforescentes y oscuros ropajes) inician entonces una larga danza que no cesa hasta que algún puerto se arroja a las profundidades

¿quién no ha visto arder el mar en esas noches?

*

mar que me bebes gota a gota

noche a noche

mar que me sorbes

desde tu eternidad amarga

*

voces que reclaman tu garganta. voces oscuras. voces que se enredan en tu lengua y en tus manos. voces que te atrapan

y te encadenan al mar

*

voces encadenadas voces que arrastra el mar de tarde en tarde

*

collar de voces que aprisiona mi garganta desde su origen tras el agua

your name . . . leaves a scar of burning boats

here. in the ocean of my breast

*

the entourage of moons remains a memory in your shipwrecked eyes

night will join us in the deepest place:

like a howl

*

the ghost of your voice

continues to call me

today

by a name already forgotten

*

on certain nights of the year—they say—a circle of golden dolphins rises to the ocean’s surface forming strange messages . . .

then the moon turns blue. slowly

*

they say when the moon is blue whole cities spring from the bottom of the sea. then their inhabitants (with phosphorescent eyes and dark clothing) begin a long dance that does not end until some port throws itself into the depths

on those nights, who hasn’t seen the sea burn?

*

sea that drinks me drop by drop

night after night

sea that sips me

from its bitter forever

*

voices reclaiming your throat. obscure voices. voices that tangle on your tongue and in your hands. voices that trap you

and chain you to the sea

*

chained voices

voices that drag the sea

from one afternoon to another

*

necklace of voices imprisoning my throat

from its home beyond the water

CATALINA SOJOS (1951)

Ruinas (fragmentos)

I

a la primera palabra le ofrecimos un poncho de espóndilos

y en sus tobillos atamos sonajeras

cuando la noche se volvió hueso

ella huyó con su aire

luego quedamos manchas

de aquellos que creímos danzar en su esqueleto

II

cuentan que el corazón del inca se transformó en aríbalo

sus fragmentos se exhiben

con esa terca actitud de las cosas que sobreviven al olvido

III

jamás sabrás quién es el vigilado

los pasos van y vienen

detrás del muro con las cinco hornacinas

arde la luna en la piedra sacrificial

hay un olor a escombro

a tierra retorcida

no, nunca habrás de saber

quién es el vigilante, el vigilado

Ruins (fragments)

I

at the first word we offered her a poncho of stressed syllables

and adorned his ankles with rattles

when night turned to bone

she and her attitude fled

later we were simply images

of those who believed we danced in her skeleton

II

they tell us the Inca’s heart retained an afterglow

its fragments are displayed

with that stubborn attitude of that which survives obscurity

III

you will never know who is being watched

footsteps come and go

behind the wall with five niches

the moon burns on sacrificial stone

there is an odor of debris

of devious earth

no, you will never know

who is the watched, who watches

JENNIE CARRASCO (1955)

Miedo

Durante toda mi vida

cargué a mis espaldas

el miedo de los hombres

no era un miedo mío

era el de mi padre

el de mi marido y de mi hermano

el de todos mis amantes

el miedo de mis hijos

Me pesaban esos temores malheridos

guerras, gritos ciegos

el fuego que al principio descubrieron

se volvió devastador

yo, mujer de aguas oscuras

de aire negro

sólo en la luna me reconocía

No era un miedo mío

yo dominaba los secretos de las flores

y los rincones más profundos

sembré y coseché

mi sangre fecunda

dio a luz la vida y la muerte

día tras día, siglo tras siglo

me parí a mí misma

Vagando en la nada pregunto

¿cómo matar el miedo de los hombres?

¿Cómo matar mi propio miedo?

Fear

All my life

I have carried men’s fear

on my back,

not my own fear

but my father’s

husband’s and brother’s

the fears of all my lovers

the fears of my sons

Those damaged fears weighed on me,

wars, blind screams,

at first the fire they revealed

turned devastating

I, a woman of dark waters

and somber air

could see myself only in the moon

It wasn’t my fear,

I owned the secrets of flowers

and hidden places,

I planted and harvested,

my fertile blood

gave birth to life and death

day after day, century upon century

I birthed myself

Wandering in nothingness I ask

how can we kill men’s fear?

How can I kill my own?

SARA PALACIOS (1955)

La ballena

La ballena sufre para ser amada

se entristece para ser amada

se emborracha para ser amada

baila, mueve las manos para ser amada

hace poemas para ser amada

y por fin . . . es amada.

Entonces

salta, con su enorme cuerpo

se hunde en el agua y se va

sin importarle nada

porque es ballena.

The Whale

The whale suffers for love

sorrows for love

gets drunk for love

dances, moves its hands to be loved

writes poems to be loved

and finally . . . is loved.

Then

it leaps, its enormous body

disappears underwater and leaves

without a thought in the world

because it is a whale.

MARITZA CINO ALVEAR (1957)

Cuerpos guardados

1

Infiel a mi sombra original

he atravesado efigies y pirámides,

me he acercado a la prehistoria

del placer

con la clarividencia de lo breve.

La sanación ha llegado,

en tinieblas

cuando menos la esperaba

devastando cábalas y adioses.

2

En este manuscrito reposan las sustancias

de antiguos ritos destinados a los mares,

de esa mitad de eternidad que me persigue

en un memorial ausente de palabras.

Esta ceremonia no es sagrada

solo un oleaje de sintagmas

en el ojal de una blusa desgastada

por el rumor del olvido y la ironía.

La otra mitad de eternidad

desconoce la rutina y el silencio,

voces que se mutan en esencias

de una escritura que conspira en mi retina.

3

Me acosa la etimología del no decir

asignando la escritura a un lugar común

repetirme en el sonido del agua,

cada vocablo me conduce al origen.

Las mismas palabras se anuncian

caricaturas en blanco y negro,

cualquier pista es una huella ausente.

Una nueva parodia me atrapa

la cotidianidad me libera.

Me entrego al sonido del fuego.

4

Dejé de escribir

con la exactitud del calendario

después de que me embalsamaran sus textos

y me convirtiera en pirámide.

Ahora lo sé

por sus olores mortales

signos de luto

que fermentan las tumbas,

mientras yo transito invertida

con otra voz que me viene,

de la escritura de un dios

que no es el dios de los muertos.

Hidden Bodies

1

Unfaithful to my first shadow

I have traveled effigies and pyramids,

approached the prehistory

of pleasure

with barely perceptible clairvoyance.

Healing has arrived,

when least expected

in shadows threatening cabalas and farewells.

2

The substances live in this manuscript

of ancient rites headed for the sea,

from this half of eternity that stalks me

with a wordless monument.

This ceremony is not sacred,

only a surge of phrases

from the buzz of irony and oblivion

in the buttonhole of a worn-out blouse.

Eternity’s other half

knows nothing of routine and silence,

voices muted in the essence of writing

conspiring in my retina.

3

The etymology of silence stalks me,

assigns writing to cliché,

repeats the sound of water,

every word takes me back to the beginning.

The same words present themselves

as black and white caricatures,

any trail is an invisible footprint.

A new parody claims me,

the commonplace sets me free.

I give myself to the sound of fire.

4

After they embalmed my texts

and turned me into a pyramid,

I stopped writing in accordance

with a precise calendar.

Now I know the signs

of keening

by their mortal odors

fermenting tombs,

while I pass by in reverse

with another voice that comes,

possessed by the writing of a god

not the god of the dead.

CARMEN VÁSCONES (1958)

Poema

El acuario revuelve la oquedad del pez

La mitad de una concha ilumina al marino

Que no pudo salir del sueño

La sirena fue una presencia inesperada

Entre cristales el cantar de los días

Sucede el carnaval

Viene la cuaresma…

La duda solloza su olvido

El cráter confiesa sobre la ciudad

Su círculo recorre la intimidad de una correspondencia

La vertiente del nudo cambia la rotación

La nevada una centrífuga del ciclo

Los ciclos de la llegada entonaron un eco de hábitos

Las historietas tras los despuntes del topo

La hiena pisa el esquema del degollador

La banda suelta día a día la torsión del tenor

El desbande aplasta algo dejado a la intemperie

Los modos del espectador resuenan en el génesis cancelado

El pasado levanta la efigie infantil

El paso de una reverencia elogia la inocencia

Con una noche oral desprendiéndose en el horizonte

El estilete recorta una hazaña

La sepultura conmemora su advenimiento

El ideal: un soplo de amor de cuerpo a cuerpo

El tribunal absuelve su propia condena

Un azar disecado en cada cuerpo

La colonia de caníbales acecha la historia

La nada: un silencio pegado a la huella

Baila sobre el cadáver del encomendado

El universo parece un ángel decapitado cayendo en el átomo

El color del círculo marcó la salida

Un deseo centrípeto acompaña la fuga

El destino se fragmenta en persecuciones

El fugitivo cruzó la frontera

Se acerca al reposo

Deja de huir

Se entrega a él.

Poem

The aquarium moves through the fish’s cavity

A half shell illuminates the sailor

Unable to emerge from his dream

An unexpected mermaid

Carnival comes around

Lent arrives

Days sing among crystals . . .

Doubt sobs its oblivion

The crater pleads guilty above the city

Circumference travels relationship’s intimacy

The knot’s gradient changes direction

Snow is a centrifuge in the cycle

Patterns of arrival leave an echo of customs

Comic books follow the mole’s dawn

The hyena steps on the executioner’s blueprint

Day after day the band turns loose the tenor’s torque

A mad rush tramples something left outdoors

The spectator’s manners sound in cancelled genesis

The past raises a childlike effigy

A passing reverence applauds innocence

With a vocal night taking leave of the horizon

The stiletto slashes a deed

Burial commemorates its accession

The ideal: a breath of love from one body to another

The tribunal absolves the sentence it hands down

Desiccated luck in every body

A colony of cannibals stalks history

Nothing: silence stuck to a footprint

Dancing on the corpse of the trusted one

The universe is like a decapitated angel falling inside an atom

Circle’s color signals the exit

A centripetal desire accompanies escape

Destiny fragments into abuse

A fugitive crossed the border

Sleep draws near

Stop fleeing

It gives itself to him.

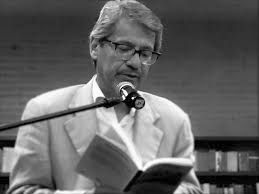

RAÚL VALLEJO (1959)

Y, ENTONCES:

Y, entonces,

¿para qué escribo?

¿para quién escribo?

La literatura debe ser un bálsamo para el estrés, no este sinsentido

que me tomará por asalto y desnudará el oxímoron en el que existo.

¿Qué valor tiene mi palabra si yo mismo soy un pozo de miedos,

polvareda que se levanta para convertirme en imagen difuminada

del ser que soy, proliferación de identidades, penitente del verso,

perenne forma en movimiento hacia nueva forma contradictoria?

Como los escritores ya no somos vanguardia de nada,

[¿es que alguna vez lo fuimos?] la política nos apesta ahora

los escritores somos mercancía exhibida en el mercado de las vanidades.

WHY DO I WRITE?

Why do I write?

For whom do I write?

Literature should be a balm for stress, not this meaningless script

that will take me by surprise, undressing the oxymoron in which I exist.

What value has my word if I myself am a well of fears,

dust rising to turn me into a blurred image

of myself, proliferation of identities, penitent of verse,

perennial voice reaching for a new and contradictory voice?

As we writers are no longer any sort of vanguard,

[were we ever] politics stink now

we are merely merchandize displayed in the market of vanities.

EDWIN MADRID (1961)

Noches de Granada

Estoy en Granada

El sol pica la piel y

tu recuerdo pica mi corazón.

¿No sé qué hago junto al Lago de Nicaragua?

Es un mar que topa los volcanes

y yo me hundo en las aguas negrísimas de tus ojos.

Voy de isleta en isleta

mirando como viven los nicaragüenses

¿Qué hago en Nicaragua,

38 grados a la sombra,

si mi nostalgia por ti

alcanza los 40 grados en la noche?

Granada,

ciudad de casas azules y verdes y amarillas

e imagino que en aquel patio de paredes rojas

tú bailas y me esperas

mas yo solo

recorro las calles

en busca de una lata de cerveza.

¿Qué hago aquí?

Gioconda Belli lee sus poemas

y Cardenal

y otros cientos de poetas

pero ningún poema dice

cuánto te extraño estas noches.

Granada Nights

I’m in Granada

The sun burns my skin and

you burn in my heart.

What am I doing on Lake Nicaragua?

It is a sea with a backdrop of volcanoes

and I submerge myself in the dark liquid of your eyes.

I go from one tiny island to another

observing how Nicaraguans live

What am I doing in Nicaragua,

100 degrees in the shade,

if my longing for you

reaches 104 at night?

Granada,

city of blue and green and yellow houses

and I imagine you in that patio of red walls

dancing and waiting for me

yet I

roam these streets

looking for a bottle of bear.

What am I doing here?

Gioconda Belli reads her poems

and Cardenal

and hundreds of other poets

but none of their poems tell

how I miss you on these nights.

ARIRUMA KOWII (1961)

Shimikunaka

Shimikunaka, kawsaytami charin

Wiñachinata, wañuchinata

Ushanllami

Shimikunaka tupu, huyaypash, kayta

ushanllami

Shimika achka kamaktami charin

Huyani nikpika

Mana riksishka pachakunata

riksichinllami

mitimay kawsaytapash

karanllami

shimika, inti, killami kan

shimika, kawsaypa llantumi

kan.

Las palabras tienen vida

tienen la capacidad de construirnos

o destruirnos

La palabra tiene tanto poder

que, por ejemplo, un “te quiero”

puede catapultarnos

a dimensiones inexploradas

o exiliarnos en el vacío.

La palabra es el sol, es la luna

es la huella

de nuestro existir.

Words are alive

they can create

or destroy us

A word has such power

that, for instance, “I love you”

can launch us

into unknown dimensions

or exile us to the void.

A word is the sun, the moon,

the footprint

of our existence.

Makipurarina

Ñawpamanta kawsaykunaka makimpurarinmi:

Samaywan rikurin, rimankuna,

Shimikunaka, samashka, achikyashka,

huanushka pachamanta shimikunami kan

shinallatak, yuyaykunaka

tamiamanta, intipachamanta wayumi kan

kay pachakunata wayllayachin

shamuk pachakunata

kawsana munaywan, watachin.

El pasado y el presente se dan la mano:

se miran serenos, dialogan.

Cada palabra es fruto

de tiempos reposados, iluminados, abonados.

Cada expresión es el fruto

de inviernos y veranos equilibrados

que hacen reverdecer el presente

que auguran un futuro asediado

por el deseo incansable de la vida.

The past and present hold hands:

look serenely at one another, converse.

Each word is the fruit

of tranquil illuminated fertile times.

Each expression the product

of winters and summer in equilibrium

causing the present to bloom

predicting a future besieged

by the insatiable desire for life.

XAVIER OQUENDO (1972)

Mi abuelo y mi abuela

tenían un caminar maduro.

Ella, pausada en el galope;

él, acelerado y discurrido.

Caminaban, mirando la última huella

que había dejado el animal de turno.

Ella seguía el paso del hombre

como una secuencia natural.

El río de mi abuelo

y de mi abuela

no se parece al Guadalquivir

ni al Guayas.

Es un río de piedra que desciende

sobre las sendas

que faltan por conocer

y adentrarse.

Mi abuela nada tiene que ver

con la abuela de Perencejo.

Perencejo no tiene esos senderos

ni ese paso seguro y lento.

El abuelo de Fulano

no conoce el camino que mi abuelo guarda

en el bolsillo:

sendero extraviado

entre la menta y el “king” sin filtro

que olían sus pantalones.

Mi abuelo se parece a los astros.

Mi abuela es un astro.

Mi abuelo se parece a mi abuela

y los dos a las estrellas.

Nada tienen del Guayas ni del Guadalquivir.

Ni de los viejos Fulano y Perencejo.

Los miramos

a través de las radiografías de sus huellas.

Miramos sus sendas como esfinges

que heredamos para practicar la fe.

Nada tienen que ver con mis zapatos torcidos.

Caminaron, los dos, el valle hasta la muerte.

Son un río que esconde a las aguas

debajo de las piedras.

My Grandfather and Grandmother

had a mature way of walking.

She hesitant in her purpose;

he in a hurry and flying.

they walked, observant of the footprint

left by the animal that preceded them.

She followed in the steps of her man

as if in natural sequence.

My grandfather’s river

wasn’t anything like

the Guadalquivir

or Guayas.

It is a river of stone that descends

over trails

yet to be discovered

and explored.

My grandmother wasn’t like

So-and-So’s grandmother.

So-and-So’s grandmother doesn’t possess those trails

nor that slow and sure step.

So-and-So’s grandfather

doesn’t know the pathway my grandfather keeps

in his pocket:

a pathway misplaced

between a mint and the King without filter

that gave his trousers their odor.

My grandfather looks like the stars.

My grandmother is a star.

My grandfather looks like my grandmother

and they both look like stars.

They have nothing to do with the Guayas or Guadalquivir.

Nor with any old So-and-So.

We glimpse them

in the x-rays of their footprints.

We look at their pathways like the sphynxes

we inherit to practice our faith.

They have nothing to do with my crooked shoes.

The two of them walked the valley to death.

They are a river that hides its waters

beneath the stones.

JULIA ERAZO (1972)

Cicatrices

¿Quién dijo que la herida estaba herida

ahora que la tierra se secó?

Carlos Otero

hay algo en ella que sonríe al subir los escalones de la casa algo que despierta la danza entre los guacamayos

algo en su mirada donde chocan las olas y saltan los peces

algo que se mueve delicado entre sus piernas

hay algo que hace salir a los sapos de entre la maleza

algo que ha dejado huellas allende sus sandalias

algo en el batir vaporoso de su falda

algo en el viento

que cruza por su cabellera

algo desfigura el paisaje

algo asusta de pronto a los sapos que se esconden

algo empuja a las aves a volar

algo desborda el brillo del océano en sus ojos

algo me inquieta

si voy detrás

algo en sus hombros

algo justo encima del cinto de su falda

algo que su blusa revela tenue en su espinazo

hay algo en esa mujer que no se justifica

Scars

Who said that the wound

was wounded

now that the earth is dry?

Carlos Otero

something in her smiles as she climbs the steps to the house

something that causes her to dance among the guacamayos

something in her expression where waves break and fish jump

something trembling between her legs

there is something that lets frogs escape into the brush

something left by the soles of her sandals

something in the vaporous movement of her skirt

something in the wind

flowing through her hair

something disfigures the landscape

something suddenly frightens the sheltering frogs

something lifts the birds in flight

something overflows the ocean’s brilliance in her eyes

something bothers me

when I follow her

something in her shoulders

something just above the waistband of her skirt

something her blouse reveals tenuous along her spine

there is something in that woman that’s just not right

respuesta acuosa

to Sandra Beraha

si las lágrimas no fueran parte del océano y las palabras no fueran los peces

y las esperas unas olas poco benevolentes y las penas el alimento que nos

desnuda el frío

y si tú no fueras el mástil y si los otros no nos alzáramos como las velas

si el planeta no fuera una brújula o un globo flotante en el vacío del universo

si la vida no fuera la ficción de otros pensamientos

si ya no durmiéramos sobre hojas transparentes y si despertáramos

al abrazo de nuevos líquidos y antiguas voces

si ya pasáramos la línea del verso y si no quisiéramos más que el simple

estado de la arena

mojados y secos

secas y mojadas

removidos y lanzadas

hundidos y montículas

watery response

to Sandra Beraha

if tears didn’t belong to the ocean and words weren’t fish

if waiting wasn’t tight-fisted waves and sorrow what keeps us from cold

and if you weren’t the mast and the others didn’t overwhelm us like sails

if the planet wasn’t a compass or globe floating in the emptiness of space

if life wasn’t the fiction of others’ thoughts

if we no longer slept on transparent leaves and woke to the embrace

of new liquids and ancient voices

if we’d already gone beyond the poem’s line and wanted nothing more

than the simplicity of sand

wet and dry

dry and wet

churned and launched

immersed and raised

ANA CECILIA BLUM (1972)

Poeticus

Escribo, porque no puedo pelear batallas con mis manos

y el lápiz—a veces—apunta mejor que la escopeta.

Escribo, porque el verbo escribir suena a única certeza,

y es ruta sin distancias, y es cuerpo sin virus.

Escribo, porque la hoja en blanco es un gato feral

y debo recogerlo, alimentarlo, darle guarida, amarlo.

Escribo, porque los adjetivos acechan y cuando matan,

también dan vida; porque el lugar común no me asusta

y lo que se ha dicho mil veces, igual salpica su encanto.

Escribo, porque todo en mí es un desencuentro:

los terminales se mudan, las calles cambian de nombre,

y nunca atino estaciones, horarios o trabajos, retornos o partidas.

Escribo porque aunque duele, no duele tanto.

Escribo, para llenar los cántaros,

limpiar los espejos,

empuñar los espacios,

caminar los laberintos.

Escribo, para no morirme de pena.

Por eso escribo . . .

Poetica

I write because I cannot go into battle with my hands

and the pencil—at times—has better aim than the gun.

I write because the verb to write sounds like the only sure thing,

and it’s a journey without distances, a body without a virus.

I write because the blank page is a feral cat

I must take in, feed, shelter and love.

I write because adjectives stalk me and when they kill

they also give life; because clichés do not frighten me

and what has been said a thousand times can also delight.

I write because everything in me is missed opportunity:

terminals switch places, streets change their names

and I never get the right station, schedule, job or comings and goings.

I write because although it hurts it doesn’t hurt that much.

I write to fill the jar,

clean my glasses,

push spaces forward,

walk through labyrinths.

I write so I won’t die of shame.

That’s why I write . . .

ALEYDA QUEVEDO (1972)

Corales

No importa la profundidad del descenso

o la imposible maleza derramada en el camino.

Es largo y frío el viaje sobre oscuros caballos.

Ejercicio de inmersión y belleza piadosa

hasta pisar altos jardines de coral negro.

Entre mi dolor -que conozco tanto desde el lodo-

y el universo poco explorado por la falta de tus palabras,

me quedan flotando la impenetrabilidad de la música y la sal.

Las medusas atrapadas entre mis pestañas me jalan rápido.

Mas no importa el precio del descenso.

Es necesario volver al camino consciente del miedo

y el aliento del océano golpeándome en la nuca.

Coral

The depth of the descent doesn’t matter

nor the impossible weeds scattered along the way.

The journey on dark horses is long and cold.

An exercise in immersion and merciful beauty

until we come to high gardens of black coral.

Between my pain -that I know so well from the era of mud-

and the universe I’ve explored little for lack of your words,

float the impenetrability of music and salt.

The jellyfish trapped in my eyelashes pull me tight.

And the price of descent matters not.

I must return to the conscious path of fear

and the ocean’s breath hitting the nape of my neck.

CARLOS VALLEJO (1973)

Carta de madrugada

Fantasma es el tiempo que besas,

beso que se ensancha y no te olvida,

humo pretérito donde hay ascuas,

ascuas que todo lo entienden y no lo dicen.

¿Conoces el relámpago varado en tu distancia?

La semilla del invierno tiembla en mis zapatos.

Oigo el amarillo entre tus pasos,

mas no sé a cuantos palmos de ti transita el amanecer.

Sé de tus mejillas que cruzan blancas

por las horas del desayuno,

y sé de las sombras de tu cielo

llenando los patios.

¿Cuántos calendarios vaciaré este día?,

¿Cómo me sostengo en este solitario sol?

Di más que un siglo, ¡dime más que un ahora!

porque tus labios conocen la fiesta

de nuestros antiguos pájaros.

¿Cuándo vuelves?

Mándame el día. Mándame noticias de tu boca.

Yo te envío un beso,

y dime, en mi comarca, ¿qué perro no te extraña?

Dawn’s Letter

You kiss a ghostly time,

a kiss that expands and won’t let you go,

past-tense smoke where embers remain,

embers that know all and don’t let on.

Do you know the lightning stranded in your distance?

A winter’s seed trembles in my shoes.

I hear the yellow between your footsteps,

but do not know how far dawn moves past you.

I know your cheeks piercing half-notes

at breakfast time,

and I’ve heard tell of your sky’s shadows

filling courtyards.

How many calendars will I empty today?

How will I stand tall in this solitary sun?

Tell me more than a century, more than a now!

because your lips know the feast

of our ancient birds.

When will you return?

Send me the day. Send me news of your mouth.

I send you a kiss,

and tell me, in my part of the world, what dog doesn’t miss you?

LUCILA LEMA (1974)

14

ñuka puriyta mana allikachinakun

yallikta rikushpa

—payka mana kaymantachu nishpa— upallakuta ninakun

kaymanta warmikunaka mana shina tiyarinchu

kaymanta warmikunaka mana shina churakunchu

kaymanta warmikunaka mana shina rimanchu

kaymanta warmikunaka mana yachaywasiman rinchu

kaymanta warmikunaka mana nataka ninchu ninakun

ñukakarin yana urkuta

tunirshka ruku wasita yarikukpipash

ñukanchik kawsakkuna

ñukanchik wañushkakuna chaykunallatak kakpipash

shukmi nishpa rikuwanakun

yallikta rikushpa

—payka mana kaymantachu nishpa— upallakuta ninakun

14

no les gusta mi caminar

me ven pasar y susurran

—ella no es de aquí—

no se sientan así las mujeres de aquí

no se visten así las mujeres de aquí

no hablan así las mujeres de aquí

no van al colegio las mujeres de aquí

no aman a otros hombres las mujeres de aquí

no dicen no las mujeres de aquí

aunque yo extraño el monte negro

y la casa vieja que ahora es tierra

aunque nuestros vivos

y nuestros muertos son los mismos

les parezco extraña

me ven pasar y susurran

—ella no es de aquí—

14

they don’t like the way I walk

they see me go by and whisper

—she isn’t from here—

she doesn’t sit like the women from here

she doesn’t dress like the women from here

she doesn’t talk like the women from here

the women from here don’t go to school

the women from here don’t love strange men

the women from here don’t say no

although I miss the black mountain

and the old house that has returned to earth

although our living

and our dead are the same

I seem strange to them

they see me go by and whisper

—she isn’t from here—

LUIS ALBERTO BRAVO (1979)

Una chica golpeada en la piscina

Su lengua ahora es más larga

y hay rastros de pasta dentífrica.

Ahora ella cierra los ojos donde lloraba.

Ahora las hojas vuelan para todos lados,

y vuelven a caer . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . cerca de aquí . . .

. . . . . . (Donde estaba la chica golpeada y muerta en la piscina).

La sacaron del agua

como quien saca a un pequeño esqueleto,

como quien carga una madera pintada . . .

O como quien mide al primer amor.

Y mientras le espiaban las nalgas . . .

—”Pero, ¿las nalgas de quién?”

—”Pues, de ella . . .

de la chica golpeada y muerta en la piscina”—.

. . . . . . alguien le sacó unas fotos;

Y por ello,

ahora podemos decir cuando nos preguntan

. . . . . . . . . . . . por la chica golpeada y muerta en la piscina:

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . “Ella estaba ahí . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Y nosotros acá . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Y los tipos de las fotos más allá”.

En la cercas pintadas

los vecinos murmuran & enrabietados

exclaman: “Si bien, era una mala chica,

no merecía morir en una piscina”.

—”Pero, ¿ha muerto quién . . .? ¿Quién ha muerto, quién?”

—”Pues ella . . .

La chica golpeada y muerta en la piscina”—.

“Yo le solía traer cervezas,

y cuando me daba propinas

ella solía decir:

.. .. .. .. .«Sólo un ángel como yo

.. .. .. .. .dejaría caer sobre ti

un pedazo de manzana…

.. .. .. .. .—Como quien deja caer sobre una isla—

.. .. .. .. .y verdaderamente lo soy»

(…) (glup)

Aún así, no tenía que morir en una piscina”.

“La mujer de allá,

nos ha dicho que a veces solía verla llorar en el patio,

y luego saltar las cercas pintadas,

sólo para arrancar —con un instrumento del bosque—

todas las manzanas fuertes”.

…

Desde aquel día

vengo a esta casa de martes a jueves…

Y siempre, siempre

un pequeño ojo del atardecer

.. .. .. …… .perfora las nubes (y luego llueve).

Y entonces… ella abre sus alas, se eleva (y llueve) y abre sus alas

.. .. .. .. . (como si evocara la luz de un perro sobre una nube podrida).

—“Pero, ¿quién? ¿Me hablas de quién?”

—“Pues, de ella…

De la chica golpeada y muerta en la piscina”—.

A Beat-Up Girl in the Swimming Pool

Her tongue is longer now

and there is a residue of toothpaste.

Where she cried, now her eyes are closed.

Now leaves fly everywhere,

and fall again . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . nearby . . .

. . . . . . . . (Where they found the beat-up girl in the swimming pool).

They pulled her from the water

as one retrieves a brief skeleton,

as one recovers a piece of painted wood . . .

Or measures first love.

And while they gawked at her buttocks . . .

—”But, whose buttocks?”

—”Well, hers . . .

the beat-up girl in the swimming pool”—

. . . . . . . . someone took some pictures of her;

And so, when they ask, we can say

. . . . . . . . . . the beat-up girl dead in the swimming pool:

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . .”She was there . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . And we were here . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . And the guys who took the pictures over there.”

By the painted fences

the neighbors murmur &

exclaim enraged: “Even if she was a bad girl,

she didn’t deserve to die in a swimming pool.”

—”But who died . . .? Who died, who?”

—”Well her . . .

The beat-up girl in the swimming pool”—

“I used to buy her beer,

and when she tipped me

she’d say:

. . . . . . . . “Only an angel like me

. . . . . . . . would let a bite of apple

fall on you . . .

. . . . . . . . —Like one who lets herself fall on an island—

. . . . . . . . and I truly am one”

( . . . ) (glup)

Even so, she shouldn’t have died in a swimming pool.”

“The woman over there,

told us she sometimes saw her crying on the patio,

and then jump the painted fences,

just so she could uproot—with a basic tool—

all the crabapples”.

. . .

Ever since that day

I come to this house from Tuesday to Thursday . . .

And always, always

a small eye at evening

. . . . . . . . pierces the clouds (and it rains).

And then . . . . she spreads her wings, she rises (and it rains) and she spreads her wings

. . . . . . . . . . (as if she were conjuring a dog’s urge above a rotten cloud).

—”But, who? Who are you talking about?”

—”Well, her . . .

The girl beat-up and dead in the swimming pool”—.

SANTIAGO GRIJALVA (1992)

Despedidas para nombrarte

Estés en mí como la madera en el palito

Juan Gelman

Los años van en mi contra

me dicen que desvuelva la silueta de los días,

que me esconda en los escondrijos de una memoria

que me enciende

al sentir como golpean

se enciende,

se esconde

para que vuelvan a golpear.

Solo suena el cristal

por dentro de la lluvia

solo nace el ayer en las próximas nostalgias,

quedarse sin ser

estar tan cerca de Dios

para sentir su aliento.

Aquí llueve dentro de casa

soles nacen por debajo de la falda del tiempo.

Preguntas por el día

el volver y tu ausencia,

por el fuego de Prometeo,

las espaldas de las tortugas

y por el qué hacer después de nuestro encuentro.

Me voy apagando en esta lluvia

sobre los destellos nacientes del cielo

que cae como un manto oculto en los dedos de la luz,

vuelvo la cabeza

veo agua en mi madera,

rasguños en los dolores y cuerpo.

El fusil aguarda cargado

pero ¿qué queda después de esta guerra?

¿qué después de tanto invierno, de tanto andar errante?

Estás en mí como la madera en el palito

para no soltar la mano fría de mi espera

estoy en ti, como tú

el nosotros en nuestras despedidas.

Farewells to Name You

You are in me like wood in the plank

Juan Gelman

The years are against me,

they say they’re giving back a silhouette of days,

saving me a lair of memory

igniting me

when I feel their blows,

igniting,

hiding in fragile order

to evade more blows.

Glass sounds

within rain alone,

yesterday is only born in future nostalgias,

to be here without

getting so close to God

you can feel his breath.

Here it rains inside the house,

suns are born beneath time’s skirt.

You ask about the day,

return and your absence,

for Prometheus’s fire

the backs of tortoises

and what we must do once we meet.

Here I am burning out in this rain

in the sky’s incipient glitter

falling like an unseen blanket on fingers of light,

I turn my head

glimpse water in my wood,

scratches on pain and body.

The gun is kept loaded,

but what remains when this war is over?

After so much winter, so much wandering?

You are in me like wood in the plank

so as not to let go of the cold hand of my waiting

I am in you, like you,

the we in our farewells.

RENÉ GORDILLO (1993)

Poema incompleto

Este es un poema incompleto,

su incompletud me medio llena

el corazón y a duras penas recuerdo

el calor de las piernas de la mujer amada

la otra parte del recuerdo es otra mujer amada.

Y así me acuerdo de media nube, de medio sueño

de la media sonrisa de mi madre, del medio pasaje

en el colegio y la media vista de la ciudad en la media terraza.

El medio mar y la media montaña,

la media aritmética, media de tabacos,

el trabajo a medio tiempo que quise para escribir más y mejor

la media palabra con la que me hubiese resignado para no irme.

Este poema fue hecho con todas las mitades que le faltan,

como todos los poemas es un retazo que no le toca ni el amor ni la tristeza

porque son palabras, palabras que si pudieran matarnos de una

vez lo harían.

Pero gracias a Dios, qué bueno esto de escribir la historia de lo

incompleto

para que la nostalgia, si viene, nos tome por partes.

Incomplete Poem

This is an incomplete poem,

its incompleteness fills my heart

halfway and I barely remember

the heat of my beloved’s legs,

the other half of that memory belongs to another woman.

And so, I remember half a cloud, half a dream

my mother’s half smile, the half landscape

of school and half view of the city from half a balcony.

Half a sea and half a mountain,

half arithmetic, halved cigarettes,

the half-time job I wanted so I could write more and better,

the half a word that would have kept me from leaving.

This poem was made with all the necessary halves,

like all poems it is a remnant untouched by love or sorrow

because it is made of words, words that would kill us

if they could.

But, thank God, it’s a good thing to write a history

of the incomplete

so that nostalgia, if it comes, only overcomes us by halves.

JUAN SUAREZ PROAÑO (1993)

Enseñanzas

En la infancia quisieron enseñarnos

el color del cielo

pero jamás nos mostraron

las nubes de humo, no dejaron entrar

el sol de las despedidas.

Nos enseñaron los nombres

y ocultaron su sangre,

aprendimos a deletrear la historia

y repetimos hasta el cansancio

las capitales de la belleza,

los himnos de pájaro exiliado.

Nos enseñaron las palabras de perdón

solo para que pudiéramos repetirlas

cuando amábamos la protección

de la noche.

Nos enseñaron a sumar las culpas

pero nos ocultaron el resultado

de frotar dos rocas

o dos cuerpos

hasta que surja algo.

Nadie nos enseñó

que podían expulsarnos

de dios y de la tierra

si en lugar de decir cuerpo lo mostráramos

si decíamos mar

y en el fondo

nos ahogábamos sin preguntas.

Tanto nos enseñaron.

Pero siempre hubo una ventana

que no pudieron tapiar

con años y pizarras:

por esa ventana

entraba a veces

a conversar el mundo.

Teachings

When we were young, they wanted

to teach us the color of the sky

but never showed us

its towers of smoke, didn’t include

the sun of its goodbyes.

They taught us names

and hid their blood,

we learned to write history

repeat again and again

those beautiful names of capitals

and the hymns of the exiled bird.

They taught us words of forgiveness

so that we could repeat them

when making love

to night’s solace.

They taught us to list our sins

but hid what happens

when two rocks

or two bodies came together

and something new is born.

No one taught us they could expel us

from god and earth

if instead of saying the word body

we revealed it,

or said the word sea

and drowned unquestioning

in its depths.

They taught us so much.

But there was always a window

they couldn’t brick over

with years or blackboards:

through that window

the world sometimes

came to talk.

[Todas las fotografías han sido tomadas de la red mundial sin ánimo de infringir en cualquier derecho legal. Por favor contactarnos para incluir créditos o remover imagen.]

[Página preparada por Ana C Blum y corregida por Lizette Espinosa.]